|

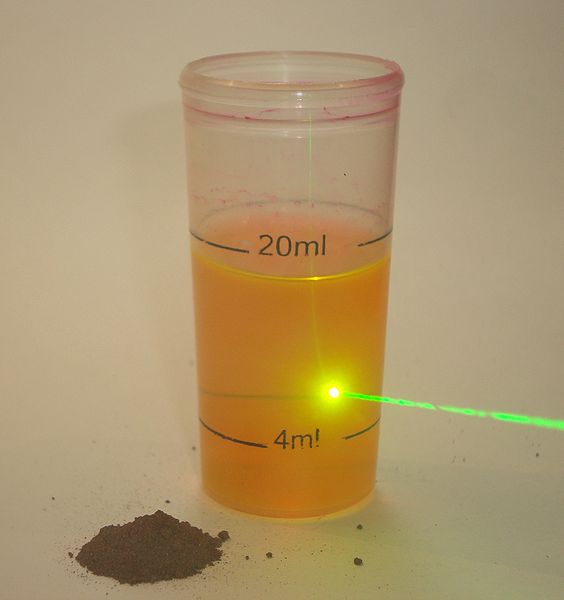

A dye laser is a laser which uses an organic dye as the lasing medium, usually as a liquid solution. Compared to gases and most solid state lasing media, a dye can usually be used for a much wider range of wavelengths. The wide bandwidth makes them particularly suitable for tunable lasers and pulsed lasers. Moreover, the dye can be replaced by another type in order to generate different wavelengths with the same laser, although this usually requires replacing other optical components in the laser as well. |

Dye lasers were independently discovered by P. P. Sorokin and F. P. Schäfer (and colleagues) in 1966.

In addition to the usual liquid state, dye lasers are also available as solid state dye lasers (SSDL). SSDL use dye-doped organic matrices as gain medium.

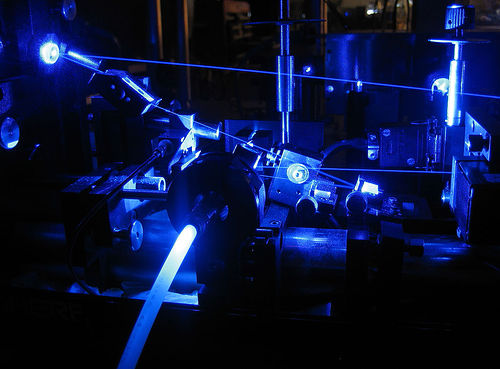

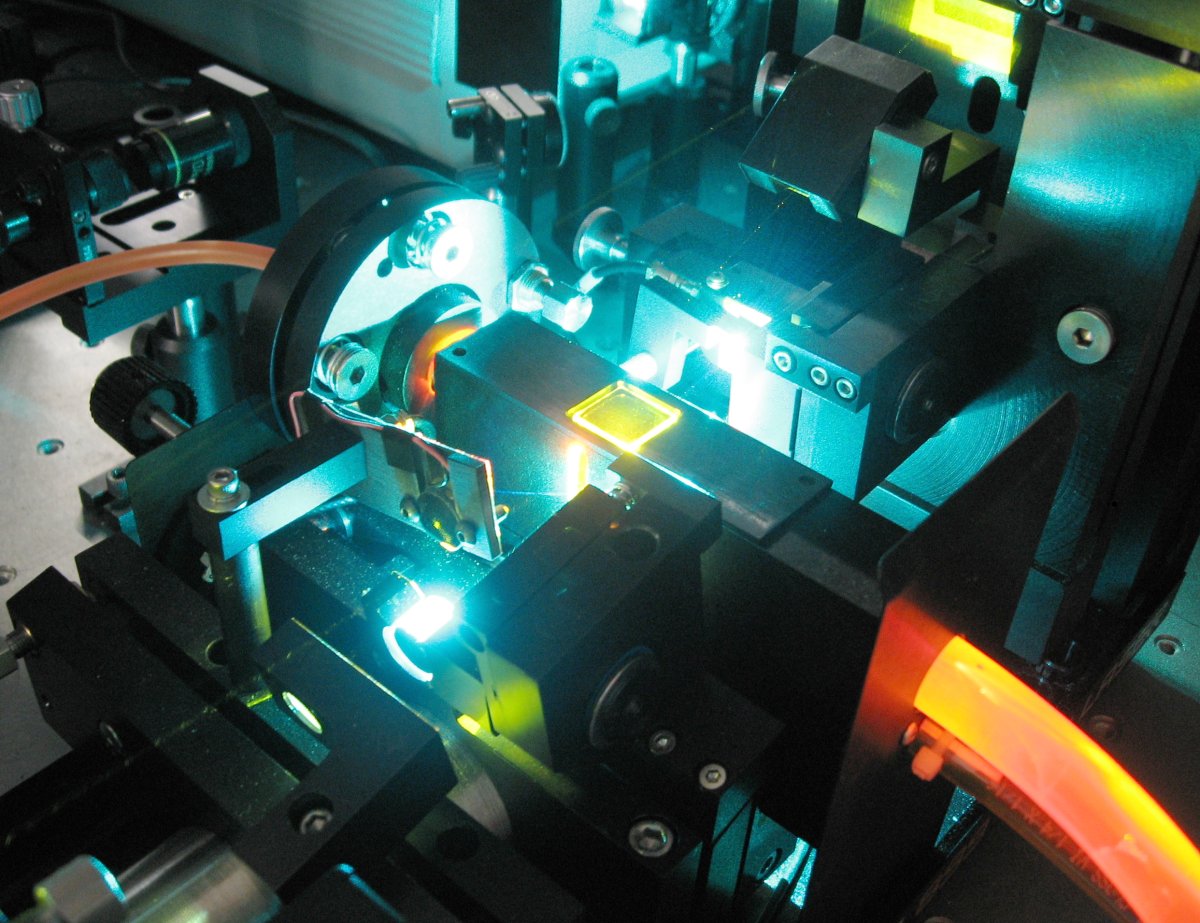

A dye laser consists of an organic dye mixed with a solvent, which may be circulated through a dye cell, or streamed through open air using a dye jet. A high energy source of light is needed to "pump" the liquid beyond its lasing threshold. A fast discharge flashlamp or an external laser is usually used for this purpose. Mirrors are also needed to oscillate the light produced by the dye’s fluorescence, which is amplified with each pass through the liquid. The output mirror is normally around 80% reflective, while all other mirrors are usually more than 99% reflective. The dye solution is usually circulated at high speeds, to help avoid triplet absorption and to decrease degradation of the dye. A prism or diffraction grating is usually mounted in the beam path, to allow tuning of the beam.

|

Some of the dyes are rhodamine, fluorescein, coumarin, stilbene, umbelliferone, tetracene, malachite green, and others. While some dyes are actually used in food coloring, most dyes are very toxic, and often carcinogenic. Many dyes, such as rhodamine 6G, (in its chloride form), can be very corrosive to all metals except stainless steel.

A wide variety of solvents can be used, although some dyes will dissolve better in some solvents than in others. Some of the solvents used are water, glycol, ethanol, methanol, hexane, cyclohexane, cyclodextrin, and many others. Solvents are often highly toxic, and can sometimes be absorbed directly through the skin, or through inhaled vapors. Many solvents are also extremely flammable.

Adamantane is added to some dyes to prolong their life.

Cycloheptatriene and cyclooctatetraene (COT) can be added as triplet quenchers for rhodamine G, increasing the laser output power. Output power of 1.4 kilowatt at 585 nm was achieved using Rhodamine 6G with COT in methanol-water solution.

|

A ring laser design is often chosen for continuous operation, although a Fabry–Pérot design is sometimes used. In a ring laser, the mirrors of the laser are positioned to allow the beam to travel in a circular path. The dye cell, or cuvette, is usually very small. Sometimes a dye jet is used to help avoid reflection losses.

The dye is usually pumped with an external laser, such as a nitrogen, excimer, or frequency doubled Nd:YAG laser. The liquid is circulated at very high speeds, to prevent triplet absorption from cutting off the beam. Unlike Fabry–Pérot cavities, a ring laser does not generate standing waves which cause spatial hole burning, a phenomenon where energy becomes trapped in unused portions of the medium between the crests of the wave. This leads to a better gain from the lasing medium.